Ubuntu in the Rainbow Nation

Seven Years of Ancestral Bows

“Become a Zen monk and join my monk army!” exclaimed Zen Master Seung Sahn, a grand master of the Korean Zen lineage based in South Korea. I was 21 years old and I had just completed the mandatory three-month silent Zen retreat before being accepted to be a novice monk. The year was 1994 and South Africa was just about to hold its first democratic elections. There was electricity in the air and a sense of heightened anticipation. We had just opened a new Zen Centre and the Zen Masters were on their way to Hong Kong. I was trying to decide about staying in South Korea and becoming a Zen monk or going home to South Africa.

We had a Zen interview in a crowded airport. I was petrified as Seung Sahn had this dynamic, volcanic energy with equal parts compassion and volcano. He shouted at me to join his ‘Zen army’. I replied “no!” He was surprised. Everyone was shocked and no one more than myself. In that moment, staring into Seung Sahn’s eyes, everything became clear for me. I needed to return to South Africa, vote for Mandela and look for a sangoma teacher. I felt the call to become an African dancing monk, a sangoma, more than a Zen monk in South Korea. I had experienced the dreaded ‘twaza’ or calling illness for over three years and, after three months of meditation, my path felt very clear. I couldn’t presume a sangoma would apprentice me, but I could at least return home and go for a traditional sangoma interview. I had experienced Zen interviews for years. Could the sangoma equivalent be any scarier?

I enrolled as a psychology student at Rhodes University. In my final honours year I decided to seek out a sangoma for a traditional divination. In the Xhosa language it is called ‘vumisa’, meaning ‘ancestral agreement’. It is a ceremony and the sangoma’s role is to be a bridge between the ancestral world of spirit and the mundane world of the here and now. MaMngwevu went into a trance as she spoke isiXhosa in a rapid way, beseeching her ancestors to ‘vula indlela’ or open the road so she could see my path or road in life. Mum had a similar energy to Zen Master Seung Sahn. There was an intensity to her and she seemed to draw the spirits towards her like a hurricane as she went into trance. She said I had the calling illness and had suffered for many years. She then stopped suddenly and looked at me with sad eyes and asked me what took me so long to come to her. I replied “apartheid!” She said “ahh Thixo, enkosiam” (oh God, I am sorry). She then said that they almost lost me, meaning I could have died from the twaza illness. There was a moment of deep stillness when we looked into one another’s eyes. In that moment there was no difference between us, just two humans falling in love. Afterwards she asked me if I wanted to become her apprentice. I asked her what it meant to be a sangoma. She said a sangoma was a healer and that, when I agreed to accept the calling, my ancestors would work through me and I would be able to heal people in many ways. I would also stop being sick and my body would get stronger. I then replied “Ndiyavuma”, “I agree” and so my sangoma journey began. The next day I returned for my first white beads, which I have been wearing for over 26 years.

I was amazed at the similarities between my Korean Zen Buddhist experience and African sangoma. They both connect with the divine through chanting and a practice of humility and service. In my Xhosa family, sangoma trainees would dress all in white, paint their faces with white clay and arrive at my teacher’s home to help in any way they could: Cooking for the community, cleaning the house, preparing herbal treatments, etc. In the Buddhist temple I experienced a similar attitude of service and devotion. In traditional Zen we were taught about the Zen circle with respect to the journey of enlightenment. In the traditional sangoma world we speak about ancestors and Ubuntu. Ubuntu means ‘I am what I am because of who we all are’. It is much more involved and dynamic than people realise. It also speaks about a circle in the form of a traditional kraal. The circle is a metaphor for the journey of our soul. In Nguni culture it is said that when people are born, they have to make a decision to become a human being, which means to honour one’s ancestors (roots) and connect with one’s umoya (spirit or soul). As we make a decision to connect to our humanity, then the ‘Ubuntu circle is activated’ spreading into the earth through our ancestors and into the world through our connection to the earth and one another. This is a lifelong process involving prayer and listening to dreams which speak about the growth of our soul and connection to the divine.

In 2015 I had the privilege of being invited to lead my ‘Ubuntu’ retreats at the Buddhist Retreat Centre in Ixopo, in the heart of traditional Zululand. The BRC has been at the forefront of spreading Buddhist teachings for over 30 years in South Africa. I was the first sangoma to teach at the BRC. The local Zulu communities practise a mix of traditional African religion and Christianity. The valleys are often alive with sangoma drumming and chanting. It made sense that a sangoma retreat was being called for. Buddhism has a history of merging with earth-based shamanic cultures around the world. Imagine my excitement when one of the BRC cooks asked to join my retreat. She was one of the local sangomas and would lead ceremonies part time for her community.

We started our retreat by circumambulating the stupa, a circular shrine overlooking a beautiful valley. I encouraged the group to send prayers to the community below, which comprised a number of rondavels scattered throughout the valley. I played my drum and taught people some simple sangoma chants honouring our ancestors and the spirit of our collective humanity or ‘Ubuntu’. Something started to stir in the hearts and minds of our group.

Meditation involved kneeling in front of a circular ‘earth shrine’ which I made to honour life. When we talk about ancestors in traditional African culture we refer to our own blood ancestors first out of respect. Animal spirit guides or totems, in addition to nature spirits and spirit guides are also often referred to as ‘ancestors’. As we take a moment to honour our ancestors we enter into a deeper relationship with nature and the earth. We see ourselves as a link in a chain of DNA spreading into the past and future. This honouring opens up our emotional intelligence and fosters humility, which strengthens Ubuntu, our human family and the circle of life.

I completed the circle of prayers to our collective ancestors by placing some snuff tobacco on the altar. I spoke in English and isiXhosa. I then passed the yellow snuff container to Gogo Mandlovu. She spoke gently in isiZulu with a quiet reverence and humility. After a while her voice became deeper and then she started to shake and an unearthly scream descended on her. I felt the presence of Gogo’s ancestors in the room and felt blessed by this visitation. I calmly told everyone not to panic, that we were experiencing the depth and beauty of South African traditional spirituality because Gogo Mandlovu’s ancestors had decided to speak to us. I asked everyone to go onto their knees, place their hands together and lower their heads with respect. We held this posture for a few moments and within a few minutes the room was transformed into a traditional South African shrine house. Gogo started speaking in a low guttural voice as one of her male ancestors came through her. They said it was the first time in their lives that they had experienced such respect from white people and the spirit said ‘ndiyabonga’ (thank you!). The whole room was filled with tears and the spirit of Ubuntu ignited the hearts and minds of everyone. I saw this as a wonderful omen. People were ready to learn the mysteries of African traditional spirituality.

Over the years Gogo and I sat together and experienced the multicultural rainbow of our new South Africa as people from different backgrounds and cultures did at our ‘Ubuntu’ retreats. People laughed and cried together. One man from an Indian background said to me: “I am 60 years old and I have done many retreats in my life. This is the best retreat I have experienced.” I was deeply humbled by this. It encouraged me to keep sharing these old ‘Ubuntu’ teachings. An important aspect of the retreat is the presence of the circular earth shrine in the centre. I also give each person a chance to speak and call in their ancestors. Every person and ancestor is equal to the next and every person adds to the circle. In isiXhosa Ubuntu is seen as umntu, ngumtu, ngabantu, translated as a person becomes a person through other people. I encourage each person in the circle to listen carefully to the person speaking in the centre. I suggested that people speak in their mother tongues because it is the language of their heart. At one point we had three people in the centre of the room praying in Polish, isiZulu and Afrikaans. It was incredible!

When the drums rolled and we danced outside, people were a bit reserved in the beginning. However, they quickly got the hang of it. Dancing is important in traditional African spirituality as a vehicle to deeper states of consciousness. We dance and chant. A number of participants over the years had sudden epiphanies and ancestral visitations whilst dancing and singing overlooking the beautiful Ixopo valley below us. In those moments I felt very proud to be a South African and share these sacred teachings.

On the eve of one retreat a few years ago, a clinical psychologist with a Xhosa background said that, when she booked to go on the retreat, she had no idea that a white guy would help her to connect with her ancestors. I said that when I was studying to become a psychologist, I had no idea a traditional Xhosa sangoma would help heal me and connect me to my ancestors. I recounted a wonderful phrase in isiXhosa, “Izinyanya zimangaliso”, the ancestors work in mysterious ways. We both laughed; the monkeys outside chattered and danced and the spirit of Ubuntu beckoned us closer.

John Lockley is a traditionally trained sangoma in the Xhosa and Swazi lineages. He apprenticed for 10 years under MaMngwevu, a Xhosa sangoma in the Eastern Cape. He has pioneered the bridge between modern western Psychology and traditional South African spirituality. His Xhosa name given by his teacher is ‘Ucingolweendaba’ meaning ‘the messenger or bridge between people’. For the last 12 years he has been facilitating ‘Ubuntu’ (Humanity) and ‘Way of the Leopard’ retreats worldwide, teaching people how they can reconnect to their Ancestors, Spirit and the Earth. John’s passion is teaching people indigenous African medicine to help them reconnect to the earth. He facilitates this through his ‘Dreams & Tracking’ retreats in the Kalahari Desert every year and his retreats at the Buddhist Retreat Centre in Ixopo, South Africa. John’s website is www.johnlockley.com. John’s book ‘Leopard Warrior’ and audio teaching course ‘Way of the Leopard’ are both produced by Sounds True and available in leading bookstores, amazon and kindle. You can also get it directly via John’s website: https://www.johnlockley.com/press.

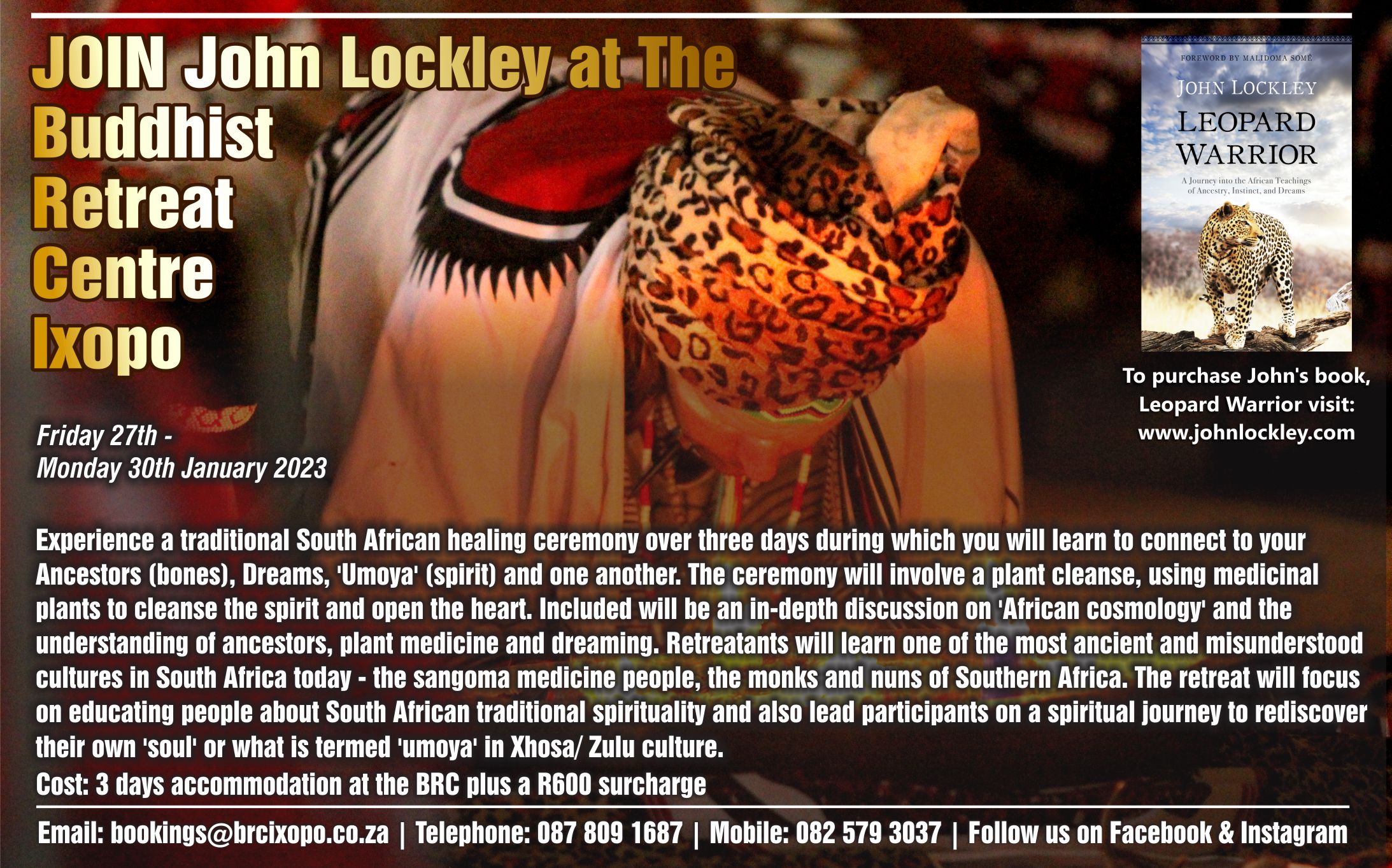

John will be leading another series of retreats in the Kalahari Desert in 2023. He will also be running an intensive 3 day ‘Ubuntu’ retreat at the BRC (Buddhist Retreat Centre) in Ixopo, Natal from 27th – 30th January 2023. Visit John’s website for more information, or to sign up for his newsletter: https://www.johnlockley.com.

John Lockley is a traditionally trained Xhosa sangoma and travels the world teaching indigenous medicine and running ‘Ubuntu’ (humanity) retreats. John’s website, Website

John’s book ‘Leopard Warrior’ and audio teaching course ‘Way of the Leopard’ are both produced by Sounds True and available in leading bookstores, amazon and kindle.

John Lockley Books