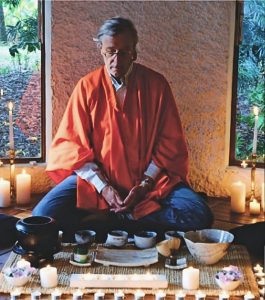

By Louis van Loon – Odyssey Summer 2019

“You may wonder, should this not be looking back? On the contrary, Louis’ teachings are as timeless as is the art of retreating, spanning past, present and future, and suggest that meditation originates from within a space where time is not a linear progression, but rather a simultaneous continuum.

Ed

Meditation. Is it as inane as watching the grass grow?

When I was busy building the Buddhist Retreat Centre, a friend of mine was puzzled and asked me why I would want to do something like that. To spend so much time, energy and money on building a lovely country resort and invite people to sit quietly on black cushions, doing nothing – just watching their breath. “This, surely, was as loony as watching the grass grow,” he said.

He was a dynamic businessman and very successful in running a string of clothing factories and shops. I had created one of the primary architectural and structural engineering consulting practices in South Africa, with branch offices in other parts of Africa. To him, the idea of withdrawing from such achievements and reflecting on the deeper meaning and purpose of life was a waste of time. He wanted to advance and expand – not retreat or withdraw.

A similar dilemma happened 2 500 years ago when Siddhartha Gautama, the future Buddha, decided to become a mendicant Yogi rather than wallow in the luxurious life that awaited him as the son of a wealthy landowner in northern India.

Siddhartha’s father had been told by a Yogi that his son would become one of the greatest gurus of all time. Even so, this was bad news for dad. He had visions of his son succeeding him and expanding his empire – not abandoning it for some nebulous nirvana.

We all come across similar choices at some stage in our lives, even if they are not quite as dramatic as that. It often happens when something painful pounces on you. This may lead you to some reflection: Is life just a relentless succession of random and painful experiences alternating with pleasant ones, or is there a larger purpose lurking behind them that you need to uncover to make it all meaningful?

This is what happened to me when I was still very young. I experienced the very painful years of the Second World War in Holland when my family, along with most Dutch citizens, was reduced to poverty. Although I did not know it at the time, this is where I believe my journey into Buddhist philosophy started: In suffering (Dukkha) – the first of the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths. The other Truths spell out the psychological processes and mental disciplines that can be learnt to enable us to deal with suffering wisely and effectively.

That is why the Buddha’s philosophy has endured so vigorously for 25 centuries. It tackles the most fundamental human experiences – the ones that underlie our everyday lives: The way we deal emotionally and mentally with needs and wants; our likes and dislikes and the way we delude ourselves and misunderstand situations – deliberately or otherwise – and helps us to navigate our way through circumstances, particularly the unpleasant or challenging ones and, in doing so, to get to know ourselves – and the world – at greater depth.

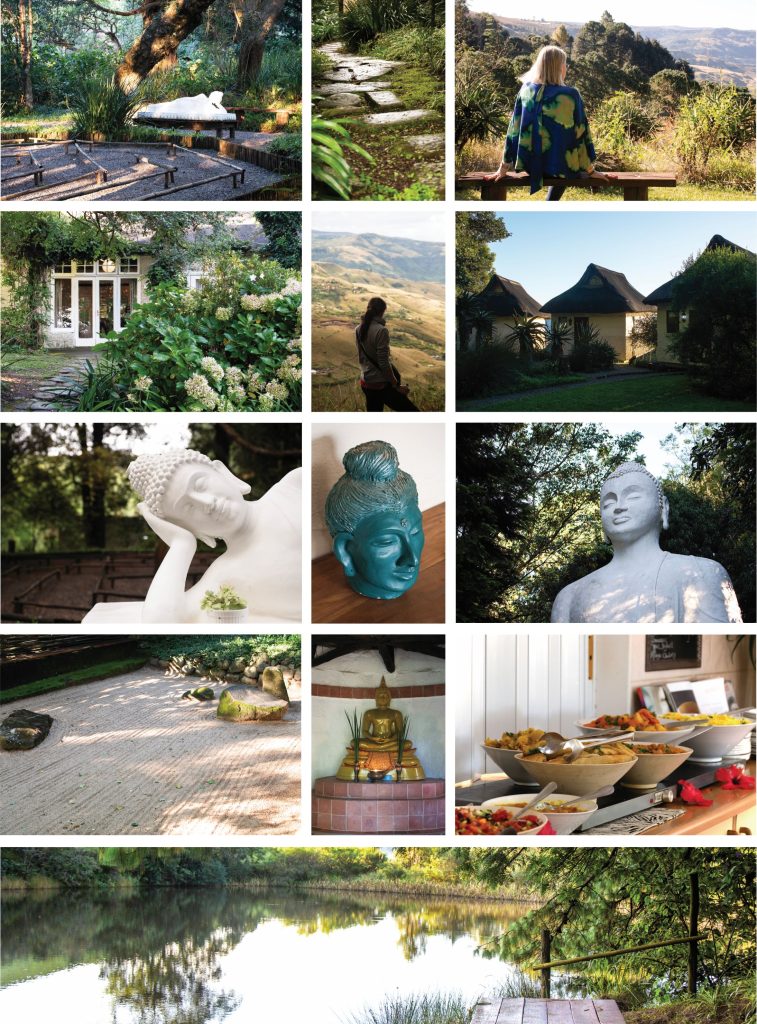

So – what does it mean to retreat? To me and to Chrisi, my wife, who has been at my side for almost 33 years? And to the thousands of people who have experienced, often for the first time, what it is like to sit on a black cushion for half-an-hour or more, letting go of the thoughts that randomly and relentlessly elbow their way into your awareness – only to return almost immediately? The Retreat Centre offers a range of retreats to equip us with powerful mental and psychological tools to bring clarity in these issues. They range from those investigating Buddhist thought and philosophy, through to meditation; as well as those featuring bird watching, cooking, pottery and photography. At first glance the latter might appear to be unrelated to Buddhism, but even these retreats will contain some element of mindful awareness, refracting the chosen subject matter through a Buddhist lens.

People from all walks of life come to these retreats with a variety of motivations and expectations. Perhaps they want to deepen their meditation practice, to take some time out from a hectic working life; to reflect on a tense domestic situation; to consider the trajectory of their lives; to decide about a way forward. Maybe they just want to learn how to take a good photograph or prepare a great vegetarian meal. Each person will have a different reason for going on a retreat. Different paths will have led them to this place.

The 13th century Zen master Dogen advises: “Take the backward step and turn the light inward.” It’s a good description of the retreat experience, particularly one with a focus on meditation. This is not a selfish practice; as Dogen says elsewhere: “To study the Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to perceive oneself in all beings, to be enlightened by all things. To be enlightened by all things is to remove the barriers between oneself and others.”

There is a story about the famous psychiatrist and thinker Carl Jung. A patient called urgently wanting an appointment for the next day. However, Jung already had a booking for that time so an appointment was made for a later date. The next day at the preferred appointment time the patient was walking in the park when suddenly he came across Jung sitting on a park bench. The patient became angry. “You told me you had an appointment!” “I do,” said Jung. “With myself.”

We all need to make an appointment with ourselves from time to time. To re-connect with who we really are; to maintain balance; to recharge exhausted batteries. To make time to go on a retreat is a necessary and healthy step for anyone.

A few thoughts on retreating

“Take the backward step and turn the light inward.” The BRC provides the space for that backward step, for the light to turn inward. During a retreat everything is designed to allow that process to occur – this is ‘time out’ from daily activities.

A weekend retreat typically begins with an introductory talk on the Friday evening and ends with a guided loving kindness meditation in which one deliberately projects kindness and compassion to all beings, including ourselves. A retreat has a dynamic all of its own – and this dynamic will be different for each person – but, like a good film or a book, it will probably have a beginning, a middle and an end. The overall experience can often be cathartic.

Attending a retreat is not only making a commitment to yourself, but also to the other people who have come. There is a collective, supportive energy generated during a retreat, especially in a meditation retreat held in ‘noble silence’ which creates the psychological space, to better enable us to ‘turn the light inward’. Such silence allows us to experience our inner self more fully; to drop the masks and the various other defences we often employ in our day-to-day interactions with others and also gives us the chance to experience better the world around us: The sounds of birds, the creak of trees in the wind. Raindrops. Noble silence allows one the precious release from the incessant internal dialogue that never seems to stop, not even in our dreams.

Many expect that a retreat will automatically be a blissful experience. For some it may be, but, as with anything in life, there are no guarantees.

If you are not comfortable with yourself in daily life you won’t suddenly find yourself in some magically transcendent state simply by going on a weekend retreat.

As Jon Kabat-Zinn points out: “Wherever you go, there you are”. Sitting on a meditation cushion, breathing in and out, there is no escape from who you are. That is not always a comfortable place to be. Like it or not, you are forced to confront the reality of your own circumstances.

So choose the retreat you wish to attend with care, with a sense of where you are right now, what you are looking for and what you need.

Retreats demonstrate, in a surprising variety of ways, how we can harness the clarity and calmness to engage our world of experience boldly, both the rough and the smooth – and act creatively and compassionately within it. Indeed, it is our primary task in life to navigate our way through these difficult processes wisely and, in doing so, to get to know ourselves at greater depth than would be the case if we ignored them or pretended they did not exist.

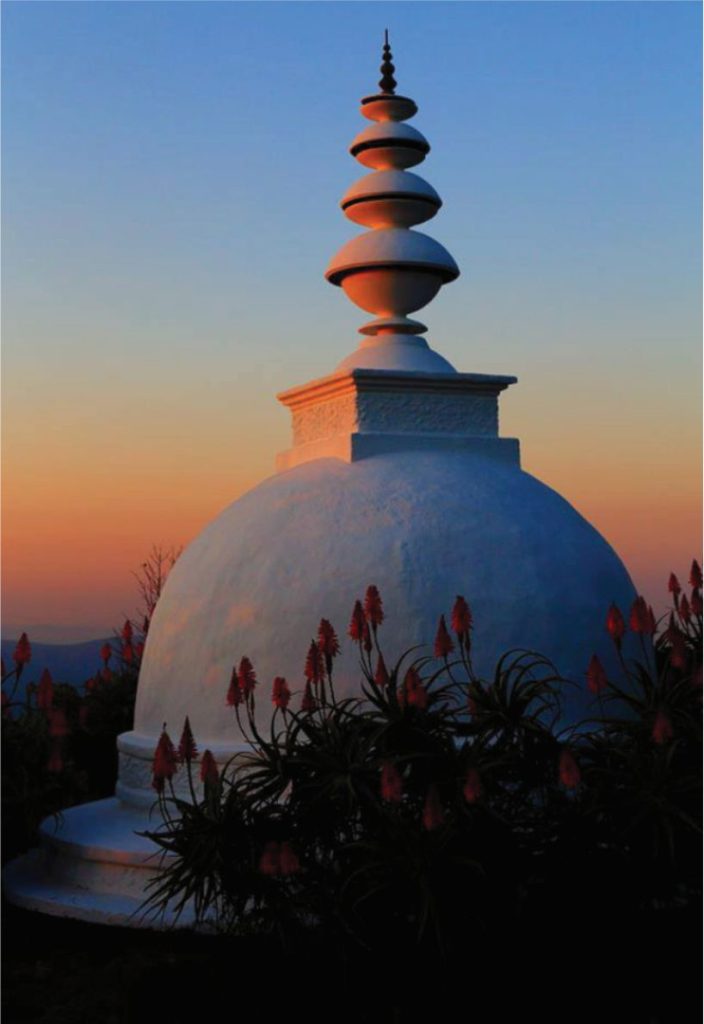

When I first envisioned the BRC 50 years ago, I intended it to become a space for people to experience what it is like just to be still and to disconnect from the daily routine of life. Simply to sit and tune in to whatever happens – to wake up – even if it is just a pigeon calling in the Erythrina tree outside the meditation hall.

The centre has become all that – and more – to the thousands of people from all over South Africa and the world who have visited. Many feel enriched by their experience and able to carry that spirit forward in their relationships with their families, their friends and colleagues and all those they meet along the ‘Great Way’ as it is called in the Zen tradition.

Honouring Louis van Loon – 1935 to 2024 – of The Buddhist Retreat Centre, Ixopo, KZN, South Africa