I have said it? Don’t believe it.”

“Belief has no place where truth is concerned.” – Jiddu Krishnamurti, 31.12.1981

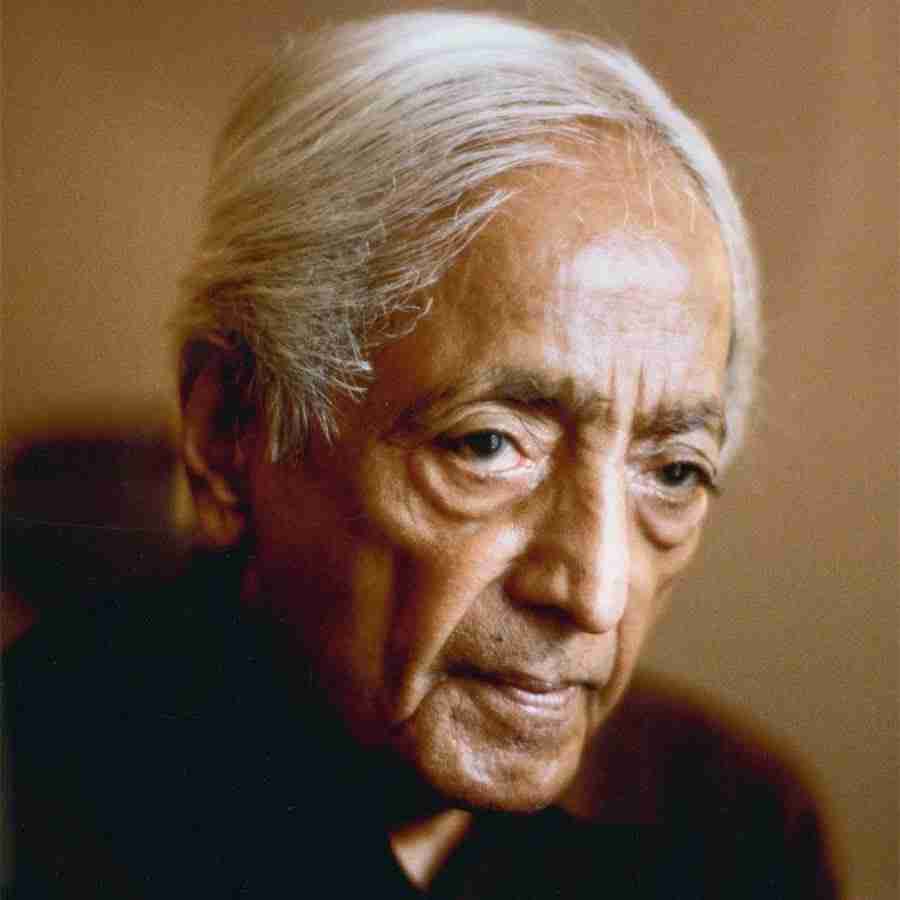

The thought leader who didn’t want to be followed

Jiddu Krishnamurti was born in the small town of Madanapelle in south India sometime between May 1895 and May 1896, birth registrations being an unreliable source of information at that time. One of 11 children, of whom six survived to adulthood, he did not enjoy robust health and suffered recurring bouts of malaria. His mother died when he was 10 years old and he regularly endured beatings from both his father, Jiddu Narayanaiah, who worked for the British colonial administration, and his teachers. Described as “vague and dreamy”, Krishnamurti was not academically inclined and his lack of attention at school was often mistaken for a lack of intelligence.

He had psychic experiences as a child, including seeing both his late mother and his sister, who had died in 1904. He described these experiences in a memoir which he wrote at the age of 18. During his childhood he developed a love of nature that was to stay with him for the rest of his life.

Two years after his retirement, Narayanaiah took a clerical positon at the headquarters of the Theosophical Society at Adyar and moved there with his sons in January 1909. There Krishnamurti met Charles Leadbeater, who described the boy as having the “most wonderful aura he had ever seen, without a particle of selfishness in it.” Leadbeater was convinced Krishnamurti would become the “vehicle” for the World Teacher whose appearance on Earth had been long anticipated by Theosophists.

Krishnamurti, along with his younger brother Nityananda (Nitya), was privately tutored at the Theosophical compound in Madras and they later continued their education abroad. He continued to have problems with school work, but showed a marked aptitude for languages. At 14 years old he learned to speak and write competently in English within six months, later adding several other languages to his repertoire, but he eventually gave up his attempts to gain entrance to university.

During this time Krishnamurti had developed a strong bond with Annie Besant, who, after a long legal battle, took custody of him and Nitya. The two boys, who had always enjoyed a close relationship, became even more dependent on each other and, in the following years, often travelled together.

The establishment of the Order of the Star in the East (OSE) in 1911 caused considerable controversy, both within the Theosophical Society and in the press. The idea behind it was to prepare the world for the appearance of the World Teacher. Krishnamurti was named as its head. However, as time went on he grew to dislike the publicity surrounding him and began to have doubts about his future.

Krishnamurti and Nitya were taken to England in April 1911. Krishnamurti gave his first public speech to members of the OSE in London and the Theosophical Society began to publish his writings. Over the next three years, the brothers visited several European countries, before their travels had to be put on hold for the duration of the First World War.

After the war, they embarked on a lecture tour to highlight the work of the OSE and its members to prepare for the ‘Coming’ and, in 1922, they moved to the Ojai Valley in California. Nitya had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and it was thought that the California climate would be beneficial. Nitya’s failing health became a concern for Krishnamurti, although he believed – and was assured by the Theosophists that this was the case – that Nitya was essential for his life-mission and therefore would not be allowed to die.

Then something happened that completely changed the course of events. On 17.8.1922, Krishnamurti complained to his companions of a pain in his neck, which worsened over the next two days and was accompanied by loss of appetite and incoherent speech. He seemed to lose consciousness, though he said later that he was fully aware and that the end of the experience was a feeling of immense peace. Then he experienced a second phase, for which he could later find no more illuminating description than “the process”. The condition recurred, with varying frequency, for the rest of his life. The “process” would lead to a state of elevated sensitivity which he most often referred to as the “otherness”.

The process had been an immensely personal thing, which neither he nor the Theosophical Society could explain. It was his and his alone and it set him in some way apart from what he had, up to then, been told to believe to be his destiny.

Nitya’s death in 1925, at age 27, came as a shock to Krishnamurti, who had lost not just his brother but also his best friend. As his vision developed, he grew further and further away from the Theosophist doctrine until, in 1929, he dissolved the Order of the Star, declaring: “I do not want followers and I mean this. The moment you follow someone you cease to follow Truth… I am concerning myself with only one essential thing: To set man free. ” Truth, he said, was not the prerogative of any sect or religion but was to be sought by each individual, through his own self-examination.

This theme was the basis of his writings and lectures for the rest of his long life, branching out into various aspects and applications, but always maintaining the need for each individual to find his or her own truth. Thus Krishnamurti often referred to his work as ‘the’ teaching and not as ‘my’ teaching.

“Organised religions throughout the world have laid down rules, disciplines, attitudes and beliefs,” he wrote in The Awakening of Intelligence. “But have they resolved human suffering and the deep-rooted anxieties, guilts?” Another warning that choosing to follow the path of others was not leading to the truth comes in one of his lectures on 31.12.1981: “You have leaders. I don’t know why you follow. You are in a jungle and you have to make your own way out.” And in The Second Krishnamurti Reader: “The constant assertion of belief is an indication of fear.”

Being on a platform didn’t give any authority to the speaker, he told an Amsterdam audience in 1969. “We are sharing our explorations together. There is no authority… To explore, there must be freedom from distortion or motive.”

But to reject the beliefs of others was not enough. You must never stop questioning your own answers. “A mind that is full of conclusions is a dead mind, it is not a living mind,” he told his audience in Ojai in 1973. “A living mind is a free mind, learning, never concluding.” Self-questioning was all-important. “The more you know yourself, the more clarity there is. Self-knowledge has no end – you don’t achieve, you don’t come to a conclusion. It is an endless river. (The First and Last Freedom)

He was definite about keeping the mind free to explore. “Mind chattering is wasting energy,” he said at Brockwood Park in 1977. “A mind that is occupied is not only useless but it has no vitality. If it’s not occupied, it’s empty and you are afraid of that. We are so afraid of being empty, of being nothing.” Paying attention to our surroundings meant observing dispassionately. “Attention has nothing to do with concentration.” In another lecture two years later, he expanded on this point. “When there is attention, there is no centre from which you are attending as there is in concentration, which then has what you call distractions. Whereas when there is attention and there is inattention, when one is aware of not attending, that very awareness IS attention. There is no distraction whatsoever.

“Thought has its own place in the field of knowledge but thought has no place whatsoever in the psychological structure of man,” Krishnamurti told his Brockwood Park audience. “Can you observe your consciousness and does it reveal its content?” Can you observe without any movement of thought interfering with your observation?” As he had observed in Amsterdam eight years earlier: “If you are looking into your own consciousness, you are looking into the consciousness of man.”

“If God made you, why are you like this?” asked Krishnamurti at a lecture on 31/12/81. “Either you have created God or God has created you… Thought has created God and now worships the image it has created, which means you are worshipping yourself.” He pointed out: “In India there are about 300 000 gods. Every local person has his own god.” He said he didn’t believe in God, “but there is eternity and for that you have to have a mind, a heart that is completely free of the burdens of life… If you love, that very love is sacred… The better part of you is God.”

Krishnamurti was also adamant that he did not want anyone to take over ‘the’ teaching, which he was handing down to the world at large.

He died of pancreatic cancer on 17.2.1986, at the age of 90, having founded five schools in India, one in England and one in California. His educational aims were to promote a holistic, global outlook; a caring attitude to nature and other people and a religious spirit.

Many of his lectures are available on YouTube. Ed and the OM Team