‘Change happens by listening and then starting a dialogue with the people who are doing something that you don’t believe is right.’

Jane Goodall, primatologist, anthropologist and UN Messenger of Peace

Walking Water has been an epic decade-long inquiry and journey made up of many millions of footsteps, countless questions and a determination to listen, harvest stories and set intentions to manifest outcomes that serve all.

For me it has been a life-changing experience and happily the journey continues with new opportunities and challenges looming large on my personal horizon.

Walkers like myself are answering a call to join a 21-day walk in September known as Lake to Lake where we’ll link California’s iconic Mono Lake and deeply controversial Patsiata/Owens Lake with our footsteps.

It is terrain we’ve covered before although this time it’ll be with the benefit of fresh insights and a willingness to view this parched world with new eyes and what is often referred to as beginner’s mind. Hopefully without prejudice or judgment.

What are the lessons? What are the opportunities? What is ours to do or be? How might we create a new and enlivening relationship with the waters and all other life?

Walking Water came into my life unexpectedly in 2013 as I completed a 124-day 2 500km walk through six European countries and four major mountain ranges as an ambassador for the World Wilderness Congress.

I’d barely arrived at the striking Congress venue in the beautiful medieval city of Salamanca, when I was approached by peace activist and water protector Kate Bunney, who asked, ”How would you like to keep on walking.” “That’s my intention,” I assured, having committed to a world walk with climate change messages about treading more lightly and lovingly upon our beloved Mother Earth.

Kate outlined her vision of a Californian source to sea walk that would attempt to start healing our broken relationship with the waters and with the indigenous tribes that are the original conservationists. Theirs is a history of living in harmony with their surroundings.

It was to be a two-year negotiation with the tribes to secure blessings to walk their ancestral lands, even though they had invariably been robbed of access to these lands and confined to so-called reservations.

Fast forward to 2015 and we were ready to take our first tentative steps on an 880km walk in three parts over three years. For me it was the deepening of a love affair with the spectacular contrasts of the land as we followed the waterways – natural and human-made – from the source high in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains to the City of Los Angeles and ultimately the place where the polluted and channelised LA River spills into the ocean at Long Beach.

The early weeks felt like a love letter to the Earth and particularly to the waters as we delighted in traversing areas of astonishing natural beauty at the time-honoured pace of our ancestors. There were also times of intense inner and outer challenge in the extremes of the desert as temperatures soared and sandstorms battered the travel-weary pilgrims.

Perhaps most challenging of all was the final fortnight walking through the city to the sea. Sleep often eluded us as we slept in city and state parks under bright lights, ceaseless traffic noise and the unrelenting busyness of the country’s second largest city.

And yet there were so many highlights, not least of which was the warmth and enthusiasm with which many Angelenos welcomed us. Many truly are angels.

Appropriately the walk started, continued and finished as a prayer and a blessing and always the intention was to build bridges between the needs of the people of Los Angeles and those of Payahuunadü, the Paiute tribe’s name for the Owens Valley.

It seemed especially auspicious that the start of Walking Water on the 1st of September 2015 coincided with a call by Pope Francis for a global day of ‘Prayer for the Care of Creation’.

As millions of people around the world bowed their heads in prayer for the wellbeing of all life on Earth – including humanity – walkers, residents, county officials and elders of the indigenous tribes sang and prayed to honour the waters and invite new ways of being in relationship with the natural world and each other.

Now we are preparing to walk again, with our group of water protectors planning to reconvene for Lake to Lake.

Significantly much of the original walk between 2015 and 2017 was undertaken against the backdrop of California’s most devastating drought and a worldwide water crisis of epic proportions. Ultimately there was a last-minute reprieve for the city when heavy snowfalls in the Sierras allowed a deluge of water to be channelled through the LA Aqueduct.

It brought welcome relief to many city dwellers, although the deprivation in the Owens Valley continues.

The valley remains parched with vegetation dying because the level of the water table has been pumped to below where the roots of trees and plants can reach.

And Owens Lake, which was sucked dry within a decade of the opening of the aqueduct, remains a bleak moonscape that is a symbol of the valley’s deprivation and a reminder of what can happen when humans try to enforce their will upon natural systems.

In 2017, the third phase of Walking Water, we resumed on the 14th of October and immediately enjoyed another synchronicity – the walkers whose numbers included representatives of the tribes, were invited to join celebrations for the newly recognised Indigenous Peoples Day. The city had decided to honour the tribes and scrap the more usual Columbus Day commemoration of the controversial colonist’s landing in 1492.

Certainly, history has not been kind to the indigenous people and part of our walk has been described as a trail of tears.

Historians point to two major events that precipitated an ocean of pain and heartbreak: 150 years ago the first white settlers arrived and forcibly displaced the native tribes who’d lived sustainably for thousands of years, while a century ago it was the turn of both the tribes and local settlers to suffer as the waters were diverted from the Owens Valley via a 377km aqueduct to grow the City of LA.

I have frequently witnessed painful reminders of the dominant settlers’ worldview. An example is the museum in the head office of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). It completely overlooks the hardships caused to the people of Payahuunadü and ignores the fact that the tribes lived sustainably and had an effective system of irrigation ditches and canals long before the arrival of the settlers. The true history of this land needs to be told.

It is a core element of the inspiring story in the documentary film Paya that was screened to walkers and guests during an evening at TreePeople.

And yet there appears to have been a slight shift recently and a growing willingness by some water and political officials, along with some senior LADWP officials, to engage.

Steve Cole, assistant director of the city’s water distribution division, joined us one evening, spoke of his love of water and answered questions. He expressed a willingness to expand on the initial contact and have follow-up meetings with Alan Bacock, water coordinator for the Big Pine Paiute Tribe.

Pivotal to his own career, which has spanned almost three decades with the LADWP, was a time of crisis in the city after an earthquake. He was refuelling his vehicle and an elderly Asian man approached him and said simply, “Thanks for what you are doing.” It was a life-changing moment and crystallised his role as a servant of the city.

As we neared the sea we walked along a cycle path flanking the LA River and were joined by a number of supporters, including several indigenous activists.

Tahesha Knapp-Christensen, an Angeleno of the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska, carried the water container that would be emptied into the Pacific Ocean on the completion of the walk.

But first there were many songs and blessings, actress Maggie Wheeler leading the Golden Bridge Choir, while indigenous elders offered their wisdom and support. Among them were the late Harry Williams, a Bishop Paiute Tribal elder, Kathy Bancroft, a Lone Pine cultural resources preservationist and Charlotte Lange of the Kuzedtika Tribe.

During the walk WW core team leader and Big Pine Paiute tribal member Alan Bacock had deeply explored the question, “Can I forgive?” Standing on the shore he appeared to have found his answer. “I love the people of LA… and that means restoring relationships,” he said.

Visionary Andy Lipkis, founder of TreePeople and an important change agent in LA, insisted, “A new city is not only possible, but also happening.”

As in any journey, there were highs and lows. Sometimes there was suspicion and even mistrust and yet we all found our way and walked on together, carried by the strength of our common care and prayer. It seems that there are the tentative beginnings of a new dialogue and the exploration of new relationships and possibilities.

“So we begin to ask what impact has our walk had?” Gigi Coyle mused. “For the walkers and those that shared parallel walks in other parts of the world, it was significant for sure. We feel solidarity of care and responsibility growing worldwide. And for those ‘in charge’, making the decisions, at minimum we hope we have awakened respect and a willingness to listen deeply.

“We will look for the people’s hearts to guide them as well as their minds, to widen the circle of awareness regarding who and what they serve, to expand their understanding of different approaches and to engage in some of the changes we and others are proposing. Time will tell.”

I believe the land and the waters of California are talking to us in ways that inspire awe, respect, intense emotions and a multitude of as-yet unanswered questions.

This is a place of extremes – the valley is one of the deepest anywhere in the United States and it is framed by the iconic Sierra Nevada and Inyo Mountain ranges. At 4,421 metres, nearby Mount Whitney towers above all other peaks in the land, while Death Valley’s Badwater Basin is 85 metres below sea level and the lowest point in North America. Furnace Creek claims to have recorded the highest air temperature anywhere in the world – 56.7 degrees C in July, 2013.

Petroglyphs carved into slabs of sunbaked rock thousands of years ago speak of the land’s power to inspire, while a disintegrating network of irrigation ditches are reminders of how the Paiute tribes lived lightly and sustainably upon the Earth long before being displaced by the arrival of the first land-hungry settlers in 1860. The valley is also a place of often extreme viewpoints, its sparse population including indigenous tribes, survivalists, conservationists, cowboys, hunters, fishers, miners, devout Christians and countless employees of the City of LA’s Department of Water and Power (DWP).

And if there is a strange familiarity for first-time visitors to these dramatic landscapes, it’s probably because this is the cowboy country memorialised in around 700 Western movies that have provided Hollywood’s glamorised take on the so-called Wild West.

I’m a relative newcomer to the Owens Valley but after many consecutive days and nights outdoors, it has woven its magic spell.

What are the messages from the soul of the Earth? That will be for us to decipher when we walk again in September.

Please support my fundraiser:

https://www.gofundme.com/f/geoffs-participation-in-lake-to-lake-2025

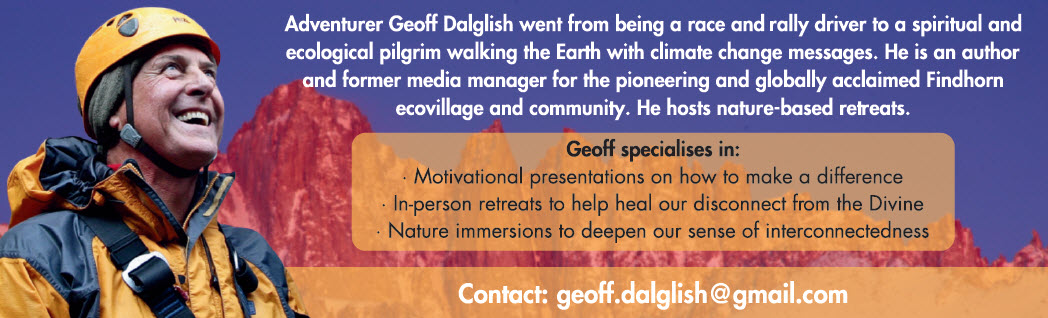

Geoff Dalglish is a writer and spiritual and ecological activist dedicated to raising consciousness. He has walked more than 30 000km with climate change messages about treading more lightly and lovingly upon the Earth. He is an ambassador for the Findhorn spiritual community and ecovillage and is Odyssey’s ‘Pilgrim at Large’.

Visit: www.earthpilgrimafrica.com