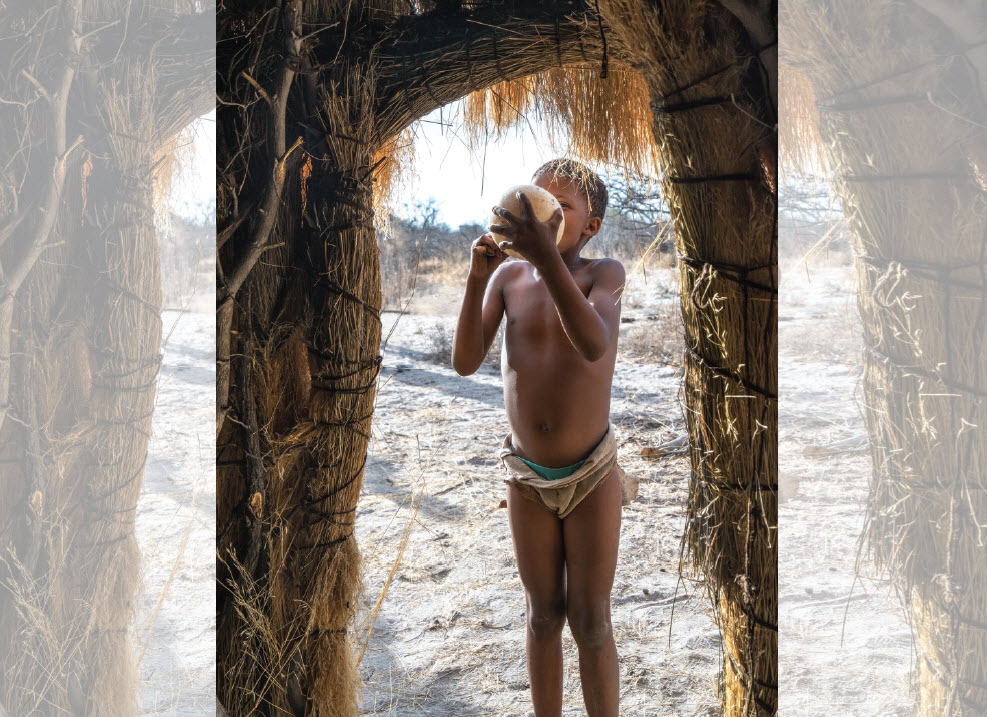

“Rain-child is a young member of the Bushmen clan I work with in Botswana and was born during a Kalahari rainstorm, which is considered lucky, hence his name.” – Clive Horlock

In the past many friends and guests, who have joined me in the Kalahari for a Bushmen cultural experience, have remarked on the behaviour of Rain-child and the other children of the clan as they never seem to need disciplining and never appear to be unhappy. The children seem to take pride in helping the adults with their domestic duties and, when not helping the adults, they will happily amuse themselves with a dry tsama melon, guinea fowl feather, or similar. It does not take long for visitors to become aware of this ‘unusual’ child behaviour, prompting the question: “How can these children always be so happy and content even though they have nothing?”

When the question is posed to Bushmen parents, they express surprise, replying: “But why should they be unhappy, children only need to be given love and safety as they are already happy?”

Does this suggest that, in our modern world, we have in some way taught our children how to be unhappy? Have our children been taught that happiness can only happen in association with a destination, event or reward?

As a parent and ex-teacher, I have always had an interest in child development and it is with special interest that I have tried to study the interaction between Bushmen adults and their children in order to try and establish an answer to this question. Making this study more relevant are two significant factors regarding the Bushmen:

Firstly, that they are considered the most successful society in human history, and secondly, that their remarkable survival lasted for tens of thousands of years, until the arrival of modern man – so, what are the secrets of their success?

Trying to understand their education methodology is therefore of ongoing interest to me and what has become clear is that child-raising involves the entire community and, at a very young age, inculcates the philosophies which shaped the Bushmen culture of survival.

Parents concentrate on providing love and making their children feel secure. This love is demonstrated through their caring, empathetic and compassionate relationship with others and through their respect for the natural world to which they believe we are all connected.

The rest of the community helps with general education and survival skills, with spiritual leaders contributing to the understanding of love by developing the understanding that all thoughts associated with love contribute to the most powerful energy in the universe, the life-force, which they call N/lom.

Details of their education processes are not necessary for the purposes of this article except for one practice of special significance, which incorporates most of the principles of the Bushmen culture.

This practice is called the ‘Healing Dance’, which was/is practised at least once a week and/or when the need arises. I originally considered this ritual to be aimed at healing ill individuals, until its real purpose was made clear to me.

The ritual can better be described as a preventative and holistic healing process aimed at maintaining physical, psychological and spiritual health, as well as to maintain community wellbeing, the health of their environment and connection with the natural world.

This description provides some insight into Bushmen behaviour and practices which form the basis of their culture. The healing dance’s purpose basically encapsulates what could be considered the ‘mission statement’ for the education of Bushmen children.

From a very young age children soon learn about the benefits of egalitarianism, sharing, giving and serving community – in essence, how to be human.

They learn to love the natural world and, as they explain: “You cannot harm what you love.” This love can be considered a ‘godly’ love, which involves empathy, compassion and caring.

They learn to suppress ego in order to avoid the social and environmentally destructive effects associated with superiority, power and greed.

They learn to be present and spend little time obsessing about the past or experiencing anxiety about the future.

They learn to connect with the energies of the universe and to benefit from universal intelligence by preventing ‘thinking’ from suppressing instinct and intuition. They learnt how to ‘be’.

Since observing and writing about Rain-child’s early education, he was required, as were all Bushmen children in his resettlement camp, to attend a local Mission School. Here he became exposed to a very different education and value system.

He encountered a culture dominated by a hierarchical and patriarchal structures. He was encouraged to be competitive, suggesting that all people are not equal and that some are better than others. Instead of believing that praise was dangerous as it boosted ego, he was taught that winners deserved praise and that individual status is more important than community. Academics became more important than all the survival skills he had been taught.

He was taught that wealth accumulation is a measure of success and that having no possessions was a sign of inferiority.

He learnt very little about the environment and was led to believe that humans were separate and superior to all that existed in nature, so much so that humans had dominion over the natural world.

His education encouraged him to prepare for a better future where happiness existed and he was always told to ‘think’, that is, to regurgitate all that he was being taught at school.

In addition to becoming obese as a result of the processed foods he was fed on, Rain-child became very confused by modern beliefs, which conflicted significantly with the indigenous beliefs he adopted from his grandparents. This led to insecurity and Rain-child abandoned school, where the smaller Bushmen children were also victimised. Sadly, he has joined the ranks of disillusioned young Bushmen who helplessly observe the genocide of their culture and mourn the loss of conscious living.

Clive Horlock spent a number of years teaching science before entering the private sector. This was followed by a stint in the corporate sector as general manager of South Africa’s first rural solar energy company.

However, throughout this time his passion remained Africa’s wildlife and wild places. This led him to establish a walking safari venture called ‘Get Real Africa’ which brought him into contact with a Bushmen clan in Botswana, an experience which had a profound effect on his life journey.

Although he does not consider himself a Bushmen expert, the ‘teacher’ in him believes that what the Bushmen have taught him needs to be shared.

To join Clive on his walks, talks and immersions,

email: horlockclive@gmail.com.