When I established ‘Get Real Africa’ walking safaris little did I know that this would ultimately bring me into contact with the closest descendants of the Earth’s ‘First People’, Africa’s Bushmen. The safari venture was established in an attempt to provide more people with an opportunity to connect with nature and to draw attention to the plight of Africa’s wildlife and wild places. In an attempt to provide the best possible experience, I began researching the possibility of finding the ultimate nature guides, Bushmen.

Bushmen is a name the last remaining hunter gatherer people of Botswana prefer to be called.

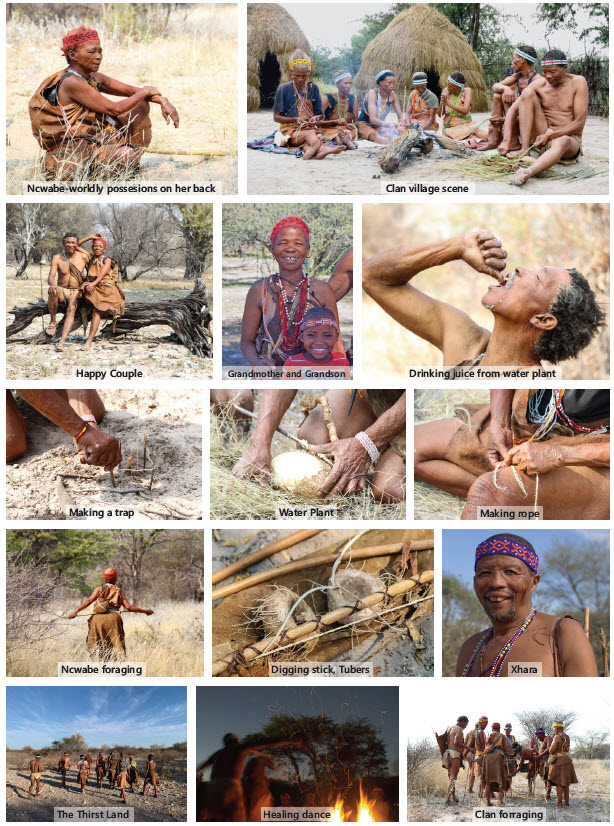

To find suitable Bushmen proved to be a difficult task as most have been removed from the lands in which they once roamed free and now have little or no opportunity to maintain their hunter gatherer culture. As a result, they are a culture in transition and facing cultural genocide. I was however fortunate in being able to locate some of the last remaining ‘authentic’ Bushmen, not just men, but a full clan, complete with men, women and children. Subsequently time spent with this group in their natural environment stirred something within me. The energy which I became exposed to, charged with joy, laughter, smoke, warmth and love, suggests that this is what humanity is supposed to be like.

A similar sense of human kindness, compassion and mutual trust I have sensed in other deep rural communities, but not to the extent experienced in the presence of the Bushmen. This proved to be life-changing for me and resulted in my focus shifting from the provision of walking safaris to Bushmen cultural experiences.

As a result of my initial Bushmen interactions many questions arose, for example:

How is it possible for people who have nothing (according to modern beliefs) to be so happy?

How have these humans managed to survive, even thrive, for tens of thousands of years without destroying their environment?

Could answers to these questions perhaps provide modern humans with solutions to the many existential threats we face today?

For those who are ‘aware’, it should not be necessary to explain what these existential threats are; they include and go way beyond just climate change. Suffice to say that leading Earth scientists warn that life on Earth is facing mass extinction and that the reason for this is human behaviour, described as anthropocentric (human centred).

In trying to find answers to the above questions, particularly regarding how the Bushmen managed to avoid destructive anthropocentric behaviour, I have become a student of the beliefs and philosophies of the ‘First People’ and have tried to compare these with those of humans today.

In this regard I have been fortunate as there is probably no better opportunity to learn about the beliefs of first humans than from the likes of some the few remaining elderly Bushmen from the Central Kalahari region of Botswana who provide a window into human history. This because they grew up with grandparents who had lived in a time and place shut off from the modern world until less than a century ago. The ‘Kalahari time warp’ is as a result of its harsh climate and absence of surface water, which made the region largely uninhabitable, except by Bushmen. Survival in such conditions earns these Bushmen the right to be called ‘masters of human survival’. To understand how they survived I have tried to understand their secrets to happiness and wellbeing.

Contrary to today’s understanding of happiness, the Bushmen seem to consider happiness as ‘a human default setting’, that is, something which already exists within us at any present moment. As such they focused on maintaining happiness rather than searching for happiness. Their culture thus developed around ways to avoid those things which caused unhappiness.

It was basically believed that human happiness was dependent upon maintaining satisfying emotional relationships with other humans, which meant avoiding those things which cause unhappiness.

To achieve this, they did all that was possible to avoid inequality, jealousy, superiority/inferiority, greed, aggression and egotistical behaviour. These beliefs translated into a culture which incorporated the following practices:

Egalitarianism, by which they believed that all people were different but equal. They respected individuality but avoided individualism.

A culture of sharing and absence of ownership as unequal ‘accumulations’ would lead to jealousy;

A necessities only policy, which ensured that consumption of any resource was limited to needs only and not wants. This served to protect their environment.

Suppression of ego, as an unmanaged ego was considered a grave threat to community survival and wellbeing. As a result, they adopted cultural practices which suppressed ego.

Khwemkjima’a (man-not-is/inhuman) was a description given to an individual with uncontrolled ego.

Community wellbeing was considered of paramount importance and to serve community, a life-purpose. It was believed that a community can survive without an individual, but that no individual can survive without community. Community support was considered essential for the physical and emotional wellbeing of individuals.

Competition was avoided as they believed it created individualism, inflated egos and split communities.

Love was considered all-important for human survival and an integral part of the life force, which they called N/Lom and which connected all life. They believed that all life forms were interconnected and interdependent. Absence of love was considered evil.

The fundamental belief was that humans were spiritual beings and that the body was merely the ‘shadow’ of the spirit and that to heal the body required the healing of the spirit.

In reading the above it should become immediately evident that our modern beliefs and cultural practices differ substantially.

In today’s world:

Egalitarianism has been replaced by hierarchical, or patriarchal structures and inequality threatens global social stability.

Happiness is considered something we seek, something external and future-related, for an example, a destination or event, or something that can be bought. Happiness has also become confused with pleasure.

Sharing has been replaced by ownership, resulting in unequal accumulations of material possessions, resulting in jealousy and envy.

The ‘necessities only’ policy has been replaced by a global economic system which relies on ever-increasing consumerism for its survival.

Suppression of ego has been replaced by inflation of egos and the exploitation thereof.

‘Community’ has given way to individualism achieved through competition, praise and hero-worshipping. ‘We’, ‘us’ and ‘ours’ have been replaced by ‘I’, ‘me’ and ‘mine’. This has resulted in the collapse of community and even the family unit. Loss of a ‘sense of belonging’ has resulted in an increase in the ‘disease of loneliness’, a mental illness.

‘Love’ has been replaced by ‘fear’ as the dominant force in society.

Today we believe that we are physical beings living in a material world separate from nature.

These cultural differences resulted in some Bushmen describing modern humans as ‘the people who walk on their heads’, a polite way of saying ‘insane’.

A combination of modern beliefs has become manifest in today’s perception of what success means. Whilst our ancestors considered success to mean the survival and wellbeing of the community and the environment, today success is mostly attributed to the individual, with material wealth and personal status being the measures used. This altered perception has contributed towards the dysfunctional self-centred human behaviour we are witnessing today.

In trying to understand how these cultural changes came about and the resulting destruction of our natural world, the following statement comes to mind:

“The most important habitat for all God’s creatures is the human mind.”

This statement inspired me to learn more about the human mind and the possible differences between the Bushmen psychological mind and that of modern humans, even though there is no biological difference. Biologists tell us that approximately 200 000 years ago, humans began acquiring cognitive functionality due to changes in the nervous system, which resulted in the development of the frontal cortex of the brain.

Prior to this, human behaviour, like that of all other mammals, was based on instinct or intuition. Acquiring cognitive functionality meant that humans acquired the ability to think.

With the ability to ‘think’ also came the birth of ego, which can be described as the ‘thinking self’ or, more aptly, ‘the illusion of self’.

Knowing the above helps us to compare Bushmen behaviour with that of modern humans.

It is evident that, whilst the Bushmen also acquired the option of listening to the ‘thinking’ mind, they endeavoured to continue listening to their instincts and maintaining their spiritual connection to Universal Intelligence.

The Bushmen claim that any wisdom they have is not their own and that their survival and wellbeing was dependent on guidance from ‘the voice with no words’ passed on through their ancestors and visions.

By contrast, modern humans have focused on intellectual growth forsaking spiritual connectivity. Whether this process can be considered natural or orchestrated is for a separate conversation but the reality is that the ‘thinking mind’ is easily programmed, making it possible for modern humans to become disconnected from the Truth and to live an illusion.

Modern man has become disconnected; from community, from the inner self and from the ineffable Truth, which exists in nature.

The dysfunctional human behaviour we witness today can be considered a result of thinking which is not in sync with the natural frequencies of the universe. This has allowed humans to behave like gingerbread men who believe that they can teach their baker.

In contrast, the Bushmen commitment to remain spiritually connected to the Universal Truth is illustrated by a ritual which they performed on a regular basis and which in essence encapsulates their cultural beliefs and behaviour.

The healing dance, like other dances, is performed around fire, and as the dancers circle the fire, their clapping, singing and shaking of their ankle bracelets serves to activate their Num (spiritual energy) to an elevated state, enabling transcendence into raised levels of awareness. Whilst in this elevated state of consciousness, they pray for holistic and preventative healing. This includes the physical, psychological and spiritual healing of each clan member, as well as the wellbeing of their community and the natural world.

Such direct connection to the ineffable Truth has largely been lost in the belief that we live in a physical world. Latest science however is now providing evidence that the beliefs of first humans are well founded. A recent quote in the London journal of quantum physics states that ‘the Earth is immaterial’ and that everything in the universe consists of energy and vibrations.

As we become increasingly aware of the impact of our dysfunctional human behaviour, we also need to take cognisance of what scientists are also beginning to say, which is that; “It is unlikely that there can be intellectual or technological solutions to our existential threats without cultural and spiritual transformation.”

The good news is the evidence provided by the Bushmen, which is that we are not born anthropocentric, it is a choice.

Also, if the Bushmen are correct in believing that ‘God did not make mistakes’, perhaps humans can once again reconnect by learning to dance to the rhythm of the universe and thereby discover our true purpose?

Clive Horlock spent a number of years teaching science before entering the private sector. This was followed by a stint in the corporate sector as general manager of South Africa’s first rural solar energy company.

However, throughout this time his passion remained Africa’s wildlife and wild places. This led him to establish a walking safari venture called ‘Get Real Africa’ which brought him into contact with a Bushmen clan in Botswana, an experience which had a profound effect on his life journey.

Although he does not consider himself a Bushmen expert, the ‘teacher’ in him believes that what the Bushmen have taught him needs to be shared.

To join Clive on his walks, talks and immersions,

email: horlockclive@gmail.com.

2 Responses

Very well written and thought provoking. There is so much to learn from the bushmen.

I had an incredible and enlightening experience interacting with this family… facilitated by Clive.

very powerful amazing history of the bushmen and they are still connected to nature.The knowledge from Clive is unbelievable.