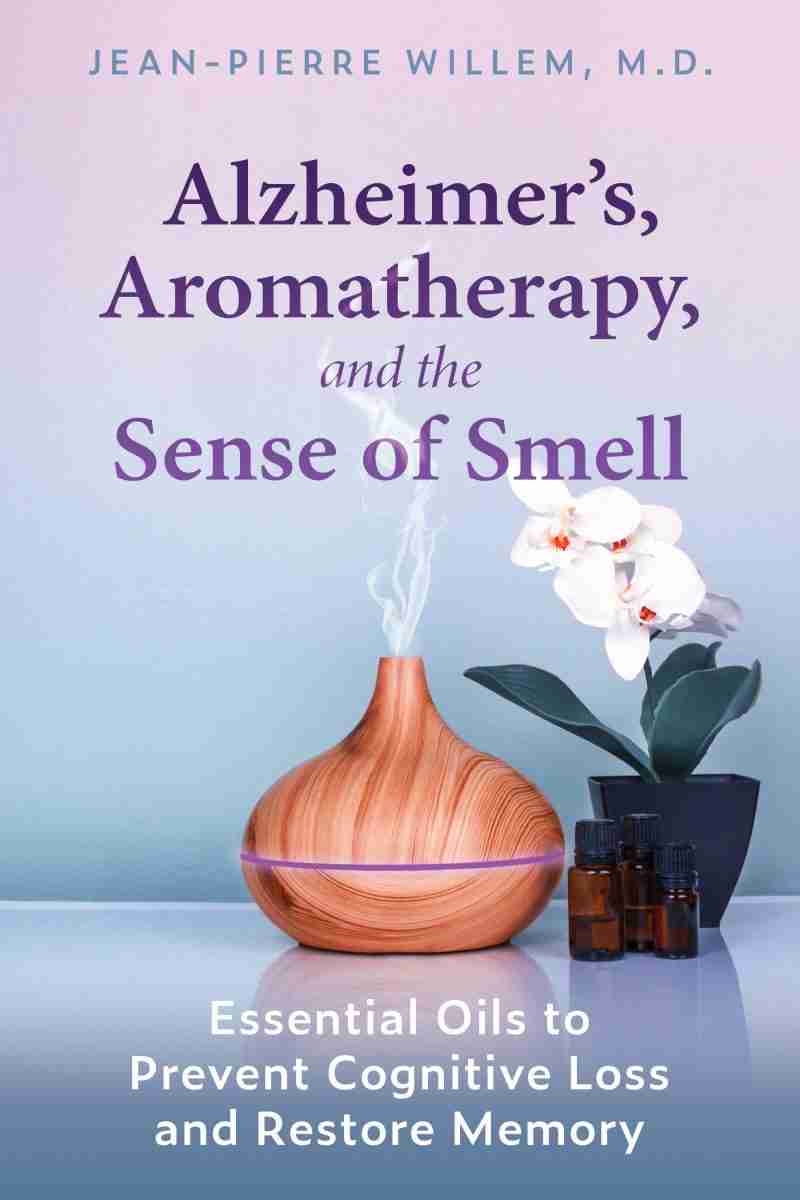

How to Use Essential Oils and Aromatherapy to Stimulate Memory and Prevent Cognitive Loss Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease

While there is still no known cure for Alzheimer’s, new research and trials from France reveal that it is possible to slow down its progression, ameliorate some of its direct and secondary effects and improve the quality of life for those suffering from this degenerative condition – all through the sense of smell. Citing years of clinical evidence, Jean-Pierre Willem, MD, shows how Alzheimer’s is critically bound with the sense of smell. He explains how the olfactory system is tightly connected to the limbic area of the brain, which holds the keys to memory and emotion and is the area of the brain most severely afflicted by Alzheimer’s. He reveals how one of the very first signs of Alzheimer’s, long before any noticeable memory loss or behaviour change, is the loss of the sense of smell. Jean-Pierre Willem, MD shares the striking results seen in French hospitals, retirement homes, assisted living and geriatric care facilities where aromatherapy has been used as a therapy for Alzheimer’s for more than 10 years. Ed.

Alzheimer’s disease decoded: Evolution of the human olfactory system

Some discoveries are made by chance or intuition, but the majority come from observations. In terms of Alzheimer’s, with its rich symptomatology, one particular clinical observation can suffice for diagnosis and should orient the direction taken by researchers: Anosmia. In fact, 95 percent of people suffering from Alzheimer’s disease are affected by the loss of their sense of smell.

No longer being able to smell the odours of nature, of those close to you, or of a perfume; no longer being able to enjoy the flavours of a dish – all these olfactory deficiencies have an undeniably adverse effect on a person’s quality of life. For clinical purposes, loss of the sense of smell comes into play in the very first stages of the disease. However, it can be difficult to evaluate this sensorial deficit because the majority of the tests used require, in addition to sensorial and perceptual capacities, cognitive abilities and an attention span, all of which tend to become dulled with age, even when no dementia is present.

Many studies have shown that patients with a genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease or those who have moderate cognitive impairment exhibit significantly greater olfactory alterations than healthy individuals. Conversely, many other studies have shown that people who present with anosmia (complete loss of smell) or hyposmia (reduced sense of smell) are more likely to develop dementia than people who retain their sense of smell.

This specific impairment of the olfactory system in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as its connection with the limbic system and the strong emotional power of olfactory memory, make a powerful argument for directing our attention toward the impact of olfactory disorders in this disease.

Employing Palaeontology

When we study phylogenesis, namely the historical evolution of the human species, we learn that our ancestors went through two major epochs: That of the raw, in which the olfactory system dominated, and then, after the discovery of fire, that of the cooked, in which the gustatory system became dominant.

Throughout evolution, every living species, particularly Homo sapiens, created defence systems in response to hostile surroundings. These genetically determined mechanisms are specific to species sharing the same biotope. One adapts to one’s environment and to one’s hostile neighbours in order to survive. Our ancient ancestors used their olfactory system (their sense of smell) as a compass to guide their survival instincts.

First epoch: The raw

In the beginning, there was the primitive diet, an ‘animal’ type of diet that was raw and intended to ensure the essentials – namely, survival, reproduction and adaptation. This raw diet was guided by the olfactory system. As Dr. Félix Affoyon, who has been studying the mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease, notes:

“It is likely not by chance that, over the course of evolution, the regions of the cerebral cortex that retained a connection with the olfactory system are the phylogenetically speaking ancient systems, such as the hippocampus of the limbic brain, which we know plays a fundamental role in the acquisition of memory, learning and the emotional aspects of behaviour, and the amygdala, which is involved in the emotions and emotional learning. It so happens that these regions are the ones that are affected in Alzheimer’s disease.”

In other words, our ancestors’ sense of smell guided their behaviour, cognitive skills and development.

Second epoch: The cooked

With the advent of cooking, humans began to face the intrusion of antigens, substances that our cells recognised as foreign and aggressive. Some paleoanthropologists maintain that this happened 20 000 years ago, in the Neolithic period, when our ancestors transitioned from hunter-gatherers to food producers. Over the course of the millennia and under the repeated assault of the foreign molecules introduced by high-temperature cooking, the olfactory system, which was our primary warning system to the presence of danger, underwent considerable genetic mutations until, slowly but surely, our ancestors’ primitive instinct for survival, reproduction and adaptation eroded. As Dr. Affoyon notes:

“If, today, human beings are no longer capable of trusting their sense of smell as they once did to avoid toxic foods and foreign molecules, it is because they altered, by chance, the course of things by discovering cooking, the transformation and preservation of foods, which over the course of evolution developed the sense of taste, gradually relegating the sense of smell to a vestigial state.”

Cooking food did some of the same work that our ancestors had previously relied on their sense of smell to do, helping them avoid pathogens (by killing them) and certain toxins (by deactivating them). Unfortunately, it also reduced certain enzymatic processes that our bodies rely on to process raw foods and it did not necessarily neutralise the full toxic arsenal found in food. Quite the contrary, for our bodies have a second filter: The intestinal immune barrier, in which wait the cells whose purpose is to detect even the smallest antigen and neutralise it. As the human species adapted over time, our increasing reliance on that antigen immune response went hand-in-hand with a decreasing use of the olfactory and limbic systems.

This is how, over the course of the millennia, a cooked diet (enjoyed no longer by smell but by taste) has produced a gradual decline and involution of the olfactory system and an inhibition of the physiological functions of the sense of smell, the hippocampus and the limbic system. To restore our olfactory function and the memory and emotion structures and processes connected to it, it is necessary to reverse direction.

There are two approaches available to us for restoring the olfactory system: Returning to a living-food diet and stimulating the olfactory system with essential oils.

Returning to a Living-food Diet

Eating raw food is one answer to current dietary shifts, a way of healthy nutrition that reconciles pleasure and health. All the animals alive on this planet, in their natural diet, feed exclusively on raw foods. We humans are the only species that cook our food – and we are among the few that are stricken by degenerative diseases, a fate also suffered by the domestic animals that share our ecosystem.

Gandhi said that in order to get rid of a disease, it is necessary to eliminate the use of fire in the preparation of meals.

Today, the virtues and pertinence of a primarily plant-food diet, one that is mostly raw, unprocessed, organic or biodynamic and preferably grown locally, are increasingly recognised by health and nutrition specialists as well as the public at large. There are still hindrances to a return to this kind of diet, mainly activated by the powerful players of corporate agriculture, agro-chemistry and large-scale animal raising. Nevertheless, the principles and foods that govern and make up the concept of a living diet have become increasingly integrated into our lifestyles. They occupy growing space on the shelves of supermarkets and speciality stores alike.

A living diet pursues the goal of giving our bodies foods that offer high nutritional density, are closest to their natural state and are easy for our bodies to assimilate. For this reason, these foods have to be plant-based and mostly raw and organic. Among the countless possibilities, several hold an important place: Sprouted grains, freshwater microalgae, seaweed, freshly extracted fruit and vegetable juices, so-called ‘green’ juices made from wheatgrass and young sprouts, oleaginous fruits and seeds and fresh fruits and vegetables that are in season and locally produced.

These living foods, which are essentially those that are high in chlorophyll and therefore have high enzyme and oxygen content, represent the purest, most original and most concentrated source of nutritive elements. Chlorophyll is the green pigment that is characteristic of the majority of plants. It is the primary vector of the life cycle because it plays a role in photosynthesis. Without chlorophyll, there would be no life on planet Earth – no plants, no animals and no human beings. In other words, the health of the human being – who is at the top of the food chain – and that of the planet are intrinsically connected. From soil to plate, all the stages share equal importance. The essential secret of a living-food diet precisely resides in this integrative or global approach to our food.

Obviously, it is not possible to eat a 100 percent raw diet. Some raw ‘foods’, like potatoes, beans, and grains, are indigestible and can be made digestible and flavourful only through cooking. This is why I recommend following a diet that is 70 percent raw food and 30 percent cooked food.

All vitamins in their ‘natural’ (raw) state are recognisable to our bodies and easily metabolised. The colloidal state of the cell in raw food is specific to its living status; cooking destroys it.

Stimulating the Sense of Smell with Essential Oils

Alzheimer’s disease is an important field of research for aromatherapy. Numerous studies already exist that reveal the value of essential oils for treating this pathological condition. For example, in Japan, researchers have observed that the diffusion of rosemary and lemon essential oils in the morning and a blend of lavender and neroli essential oils at night restores the olfactory system in elderly people after a period of 28 days. Alzheimer’s patients in this study saw improvement in cognitive function – including abstract thinking – and slight improvement in motor skills (Jimbo et al. 2009).

Essential oils and the neurosciences

Inhaling essential oils alters our cerebral activity. Many studies have shown that different compounds in essential oils have varying effects on, for example, alpha and beta wave activity, as measured by electroencephalogram (EEG). Some essential oils have stimulating effects, others have relaxing effects, and still others have different effects. But while the physiological effects of aromatic essential oils have been the subject of much research on topics ranging from brain activity to blood pressure and cardiac rhythm, the more subtle impact of odours on our minds are just beginning to be mapped out.

In Garches, France, essential oil specialists are leading workshops in the rehabilitation department of the Raymond Poincaré University Hospital. Their objective: Stimulating individuals who have been victims of a stroke by having them smell a variety of common everyday odours (cookies, toast, candy, freshly cut grass . . .). “Though a direct connection to the memory, the patients have managed, thanks to aromas, to re-appropriate a portion of their personal histories, to remember words,” notes Patty Canac, who teaches olfactory aromatherapy at the Free School of Natural and Ethnomedicine (FLMNE), which I direct. Sometimes the restoration occurs in spectacular fashion. The therapeutic value of the work has been recognised and similar work is now under way in a dozen medical centres as well as assisted living facilities for individuals suffering from Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis.

Essential Oils in a Hospital Setting

The ability to use aromatherapy as treatment for Alzheimer’s patients has been drawing the interest of a growing number of medical establishments. In France, hospitals in Colmar, Poitiers, and Valenciennes, as well mobile teams of palliative care companions in Rennes and Angers and even retirement homes, have employed olfactory aromatherapy as a treatment support in cancer, geriatrics, and Alzheimer’s. Benefits include the encouragement of sleep with lavender, soothing anxieties and agitation with petitgrain and orange zest, stimulating appetite with lemon, mood regulation with ylang-ylang and clary sage, increasing vitality with rosemary and reducing nausea or pain with ginger and peppermint. The effect of essential oils for olfactory purposes, as shown in several studies, is quite concrete. Their impact can be felt on the autonomic nervous system, the central nervous system and the endocrine system. Their effects are clearly visible on the patient’s state

Author Bio: Jean-Pierre Willem, MD, is the founder of the French Barefoot Doctors movement, which brings traditional healing techniques back into clinical settings. The author of several books in French on natural healing for degenerative diseases, he lives in France.

Alzheimer’s, Aromatherapy, and the Sense of Smell by Jean-Pierre Willem, MD published by Inner Traditions International and Bear & Company, ©2022. All rights reserved.

http://www.Innertraditions.com – Reprinted with permission of publisher.