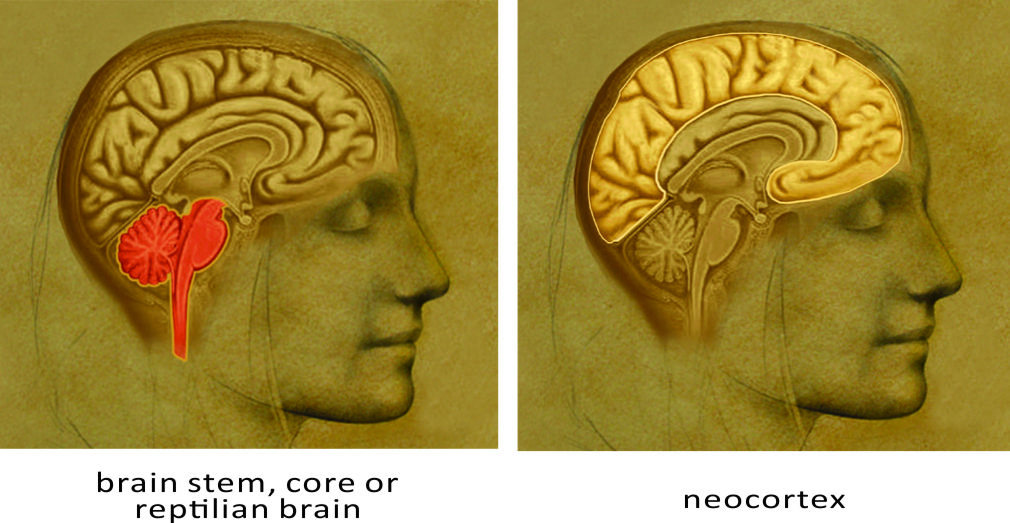

Primitive reflexes are the instinctive, automatic movements of the body controlled by the brain stem that promote survival during the early years of life. These early life reflexes lay down the architecture and neural networks of the brain and each reflex builds on those that have gone before. This results in the passing of control from the brain stem (primitive brain) to the prefrontal cortex.

The fear paralysis reflex

The fear paralysis reflex (FPR) is the key to all other primitive reflexes. It is the first reflex to manifest. FPR is a withdrawal or ‘freeze’ response to shock and lays the groundwork for more mature coping strategies in response to stress. It is intended to develop, become integrated and fall away before birth. If the FPR does not follow the proper route of development, or if a person is caught in survival response due to shock or alarm, their sympathetic nervous system will be locked in a state of fear. This will affect all waking and sleep activity. When FPR is active, all situations are (neurologically) seen through a filter of fear.

- The freeze response results in an inability to think and move under stress;

- Overcompensation for inner anxieties by attention-seeking, often in inappropriate ways;

- Chronic insecurity, phobias and fears of public humiliation, embarrassment and/or failure;

- Depression, compulsions, sleep and eating disorders;

- Rigid, inflexible, perfectionistic and controlling behaviour, with a tendency to blame others for their misfortunes;

- Outbursts of aggression or temper born out of frustration and confusion;

- Reduced muscle tone and poor balance;

- Hypersensitivity to stimuli, constant feelings of overwhelm, dislike of change, risk and/or surprises;

- Shallow, difficult breathing;

- Chronic fatigue;

- Difficulty in expressing or receiving affection.

Typically, if one early life reflex remains unintegrated, then there are usually more than one. Each retained reflex controls aspects of posture, movement, perception and behaviour. If an individual is operating from their brain stem rather than their prefrontal cortex they will have difficulties processing and analysing information and they will have coordination difficulties.

Moro reflex

An active fear paralysis reflex is often coupled with an unintegrated moro reflex. It is estimated that the majority of people suffer with either an unintegrated moro or fear paralysis reflex.

The moro reflex is a startle reflex which causes the infant to inhale and spread their hands wide with their head back and eyes wide open, followed by withdrawal. This is the primitive fight or flight response and should be integrated at about four months.

If the moro reflex is not integrated, the individual will remain in a highly stressed state for their entire life.

This can manifest as:

- Tension, emotionality and an inability to relax;

- Frequent nightmares;

- Allergies, infections and chronic pain as the liver and kidneys become stressed;

- Low tolerance of stress and resistance to change.

Asymmetrical tonic neck reflex

The asymmetrical tonic neck reflex (ATNR) emerges at around 18 weeks in utero and is inhibited or suppressed between 6-8 months after birth, while awake. It persists up to three-and-a-half years while asleep. The ATNR fulfils many purposes. It has been suggested that one of its primary functions is to assist in the birth process – the rotation of the head allows the shoulders to move and therefore the baby moves in a spiral down the birth canal. The ATNR may also help survival. When a baby is placed prone, it should not go into the “frog” position. The head should go to one side, with extension of the jaw arm and leg. This allows free passage of air.

The ATNR is the first training ground for eye-hand co-ordination. When a baby is born it can only focus its eyes at about 20 centimetres. Outside of that, the baby can see movement and shadow, but it cannot focus. Through the ATNR, the baby slowly extends the vision from near point fixation to distance and therefore this is vital for eye-hand co-ordination training.

Activation

When the head is rotated to either side the jaw arm slowly extends, the jaw hand and fingers also slowly extend. The jaw leg extends, but not as much as the arm. The occipital (the back of the head) arm and leg bend. This is the ‘kick’ the mother feels and it should get stronger and stronger as birth approaches.

Consequences

If the ATNR remains strongly present it might affect vision. The hand does not want to cross the midline and, as the eyes are locked in to the hands, they do not want to cross the midline either. This may mean that, when reading for example, when the eyes get to the midline, they ‘jump’ and the child may lose his/her place.

In crawling, the child is unable to reach and then bend the elbow to drag itself along (it is physiologically impossible to creep, commando style). In creeping, the arms need to remain straight, but the ATNR causes a bending of the occipital arm.

In grasping, when the baby looks at the object, the fingers will want to straighten out. In the older child, it is as though there is an invisible force which causes the arm and hand to straighten whenever the head is turned to one side.

The child may have to exert a great deal of conscious control when writing – something that should be automatic. In addition to the fatigue caused by the effort of fighting the reflex, the child’s comprehension can suffer, due to the cortex being involved in movement. This can, in turn, affect concentration.

Judging distance will also be difficult. If present in the legs, walking will be affected and the child will tend to walk with a stiff leg gait. When at school, catching a ball (bringing the hands together at the midline) will be affected.

When the head turns right, the left knee will bend and therefore disturb balance. Writing and copying problems will also be seen. Gross and fine muscle co-ordination and eye tracking will also be affected. Many children who are articulate and bright just cannot seem to express themselves well in written work.

It is as though the mind can think and the mouth can speak, but when a motor task is added (writing, for example) the child seems unable to demonstrate the intelligence that one knows is there.

It is clear, therefore, that the ATNR can have a very severe effect. Help – Jane Field (1992) has suggested that a child who has the ATNR will need more space to help counter the effect of the reflex – some children will write with the paper at the far side of the desk and the arm straight. To seat a right and a left handed child together at the same table will cause difficulty for the one who has the ATNR.

Symptoms suggestive of a residual or retained primitive asymmetrical tonic neck reflex:

- Balance may be affected as a result of head movements to either side;

- Homolateral (one sided), instead of normal cross pattern movements – e.g. when walking, marching, skipping, etc;

- Difficulty crossing the midline;

- Poor ocular pursuit movements, especially at the midline;

- Mixed laterality (the individual may use left foot, right hand, left ear, or

- May use left and right hand interchangeably for the same task);

- Poor handwriting and poor expression of ideas on paper;

- Visual-perceptual difficulties, particularly in symmetrical representation of figures.

Tonic labyrinthine reflex

The TLR has two forms: forward and backward. In the forward TLR, as the head bends forward, the whole body, arms, legs and torso curl inward in the characteristic foetal position. In the backward TLR, as the head is bent backward, the whole body, arms, legs and neocortex brain stem, core or reptilian brain torso straighten and extend.

The TLR provides the baby with a means of learning about gravity and mastering neck and head control outside the womb. This reflex gives the baby opportunities to practise balance, increase muscle tone and develop the proprioceptive and vestibular senses. Eventually the TLR interacts with other reflexes and bodily processes to help develop coordination, posture and correct head alignment from infancy through toddlerhood. It is critical for the TLR to do its ‘job’ because correct alignment of the head with the rest of the body is necessary for balance, visual tracking, auditory processing and organised muscle tone, all of which are vital to the ability to focus, pay attention and learn.

Possible long-term effects of an active tonic labyrinthine reflex:

- Balance and coordination problems;

- Shrunken posture;

- Easily fatigued;

- Muscle tone too weak or too tight;

- Difficulty judging distance, depth, space and speed;

- Fear of heights;

- ‘W’ leg position when floor sitting;

- Motion sickness;

- Visual, speech, auditory difficulties;

- Tendency to be cross-eyed;

- Stiff, jerky movement;

- Toe walking;

- Difficulty walking up and down stairs;

- Difficulty following directional or movement instructions.

Comment:

What is clearly evidenced in the foregoing are the difficulties that children can face. How do children (and parents) cope with these conditions if they are not recognised and timeously addressed?

The article below indicates the problem is acute and of national concern.

It might be beneficial if the Department of Basic Education were to introduce a programme of integrative exercises into their Life Skills syllabus at an early age.

Many SA kids can’t read or write

June 29 2011 By Nontobeko Mtshali, Shaun Smillie and Sapa The Star

Most Grade 3 and 6 pupils can’t count and can’t understand what they were supposed to have been taught. They scored a dismissal 28 per cent in numeracy and literacy in a countrywide assessment test earlier this year. In Gauteng, nearly 70 per cent of the province’s Grade 3 pupils can’t read or count. Basic Education Minister Angie Motshekga described the results as “very sad”.

“Provincial performance in these two areas (literacy and numeracy) is between 19 per cent and 43 per cent, the highest being the Western Cape and the lowest being Mpumalanga.”

The pathetic results confirmed earlier international surveys, in which South African Grade 3s and 6s were ranked very low and their performance was cited by educationists as a symptom of a dysfunctional education system.

Professor Sarah Gravett, the University of Johannesburg’s dean of education, explained that the language and literacy assessments not only show whether pupils read and identify words, but also if they understand what they’re reading.

The evidence is overwhelming that education is failing, the National Professional Teachers’ Association of SA (Naptosa) said.

“We have also been concerned that when samples of learners in Grade 3 and Grade 6 were involved in writing similar literacy and numeracy tests… some years ago, the results did not seem to be used to inform interventions that could possibly have made a difference,” it said.

The test now provided hard evidence on which to base decisions on “what must be done and where it needs to be done” and it was now up to the department’s officials to take action.

“The same mistakes cannot be repeated over and over again,” Naptosa said. Motshekga said the low levels of literacy and numeracy in primary schools were: “worrying precisely because the critical skills of literacy and numeracy are fundamental to further education and achievement in the worlds of both education and work.

“Many of our learners lack proper foundations in (these subjects) and so they struggle to progress in the system and into post-schooling education and training,” she said. Motshekga decided to conduct the tests after it was pointed out that the poor matric results reflected poor performance at lower grades.

The tests, which looked at the pupils’ ability to write, read and count, were written in February this year by over nine million pupils from public schools in all nine provinces.

The assessments were not used to grade the pupils, but to give the department and the education sector as a whole insight into whether the pupils know what they were meant to have studied in their previous grades.

According to the report, Grade 6 results for language – based on a sample of results from selected schools – show that as few as 15 per cent of pupils scored more than 50 per cent.

Among Grade 3 pupils, only 17 per cent scored more than 50 per cent in their numeracy assessment and 31 per cent scored more than 50 per cent in the literacy test.

Anything below 35 per cent meant “not achieved”.

Basic Education Director-General Bobby Soobrayan explained that the results will be used as “a diagnostic tool” for the country’s 25 000 public schools. He said the assessments focused on basic key foundation skills of literacy and numeracy that were “universally recognised to be key determinants of overall learner performance.”

Kathy Callaghan, secretary of the Governors’ Alliance, which represents more than 300 Gauteng schools, said that, while this was bad news, the positive was that it was now out there. “We can build from there,” she said.

Salim Vally, an education analyst, said it was a catastrophe and that it “shows that South Africa is at the bottom of the pile.”

He emphasised that the critical year for children when it came to cognitive development was in Grade R. He said much needed to be done to improve the working conditions of Grade R teachers and getting access to all children.

“Only a fraction of our kids in South Africa go to pre-primary schools and that’s a shame. This is the time of critical intervention.” –

The Star

Ray Lacey is a CranioSacral Therapist (CST) and artist. In recent years he has devoted his attention to writing, illustrating and producing books. He graduated from Natal Technikon (DUT) in graphic art and from the Witwatersrand Technikon (JUT) in graphic design. He lectured at the same faculty in illustration and then worked as a freelance illustrator for many years.

In the late 1990s he developed an interest in the interpretation of children’s drawings. This led him to study remedial therapy for children with learning difficulties within the Waldorf School movement. In 2001 he undertook training in CST and qualified in 2002. Much of his work focuses on social upliftment projects and the adverse effects of vaccines, especially in children.

YouTube link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-NDsABpJB4

Website: www.knovax.org